Vermont’s Great Flood Transcript

Back to Vermont’s Great Flood episode page.

Late in the evening of Wednesday, November 2, 1927, it started to rain in Vermont.

Pauline St. Louis: Well, I was having a day off. And I was so happy in the morning because it was raining and I love to sleep when it is raining. I thought it was beautiful.

The water came down from the mountains and pooled in the valleys. By Thursday afternoon, rivers swelled their banks.

Pauline St. Louis: I went upstreet later in the day, and a friend of mine that lived across the road had his little Ford, and he said, you better let me take you home, because if you don’t you’re not gonna get back.

Plenty of early Vermont towns had been settled on high ground. But during the Industrial Revolution, town centers were built alongside rivers to generate power. By the late 1920s, more Vermont towns than ever were situated next to the water.

Frances Ryder: We didn’t get disturbed about rising water until late in the afternoon because the Winooski has flooded almost every year anyhow. But then, of course, between 4:00 and 5:00 o’clock, people with small children began to leave their homes. They could see that there was trouble coming.

People left their homes for high ground. If they lived in town, they went to the tallest building and climbed the stairs, taking refuge on the upper floors of inns and office blocks.

Peter Guiliani: Perhaps the weirdest spectacle of the whole night was the collapse of the telephone poles in the vicinity of the post office. A loud crash would be heard , and from the windows we could see the poles lurch from the water in a blaze of light caused by the breaking wires and fall back again into the water. The entire scene would be illuminated with a ghastly red light and the scenes so revealed were weird indeed and far from reassuring. The poles continued to crash at intervals, but soon after midnight things seem to quiet down a little and not much could be heard except the rushing of the water and pelting of the rain on the skylights.

On Saturday morning, when the waters began to recede, it became clear that this was an unprecedented catastrophe. To this day, the 1927 flood is considered the biggest natural disaster in Vermont’s history. But the flood was an even bigger turning point. The rebuilding process set in place some of the infrastructure that we still use today. And right before the Great Depression and the New Deal years of the 1930s, it focused the federal government’s attention – and some of its money – on a state that had never really asked for it.

This is Before Your Time, presented by the Vermont Historical Society and the Vermont Humanities Council. I’m your host, Jen Dole. Every episode, we go inside the stacks at the Vermont Historical Society to look at an object from their permanent collection that tells us something unique about our state. Then, we take a closer look at the people, the events, or the ideas that surround each artifact.

Today, we’re going to talk about the 1927 flood. But we’ll start with a simple, household object that sounds like this:

What you’re hearing is a rug beater. You might have a rug beater lying around in your attic or basement, or maybe you’ve seen one in an antique store. Here’s Sarah Dopp, who donated her family’s rug beater to the Historical Society.

Sarah: Well, it has a wooden handle and it has four pieces of metal that come up in a long, elliptical shape, and then are sort of twisted at the top. It makes it kind of a rigid paddle ..It just allowed you to slap a carpet hung on a clothes line to get the dirt out of it.

Sarah’s talking to Mary Rogstad, the registrar at the Historical Society.

Sarah: Do you have an idea of the age of this because as with many things in my great-grandparents house, I’m sure that was there long before 1900, and in use.

Mary: Yes, they started in the Victorian era so it was mid-1800’s…

Sarah: The other thing is possibly, and I don’t know this, but possibly this is handmade. I’ve got some gardening tools that were made either by my great-grandfather or for him and I’m not sure which, that have quite similar handles to this.

This rug beater came from Sarah’s family’s house in Proctor, a town just north of Rutland on the Otter Creek. Sarah’s mother told her about using it to clean their rugs after the 1927 flood.

Sarah: Well, she was a college student at UVM at that time, and my understanding is that UVM closed down for the couple of weeks following the flood because the majority of students at that time were Vermonters, and in most cases they were needed at home.

Sarah showed us a picture of the house her mom came back to.

Sarah: I’ve got a smaller version of it here that says, “water had receded a foot when this picture was taken” and it is the same view. So it was even a foot higher than this picture.

Mary: The house was just surrounded by the Otter Creek.

Sarah told us the comments on these photos were probably written by her great-grandfather, Myron Chapin Warner. Myron lived in this house we’re talking about, and Sarah’s grandparents lived in a different house up the hill, with Sarah’s mother and aunt. When the water started to rise, Myron didn’t want to leave.

Sarah: They were all about getting him out of the house, but he was more satisfied with inching up in the house on the stairs and I guess they finally just had to lay down the law and get him out.

Myron was 85 when the flood came. He had lived in Vermont his whole life. He even fought in the Civil War, as a private in the 1st Vermont Cavalry.

Maybe you’ve seen the Julian Scott painting of the Battle of Cedar Creek – it takes up an entire wall in a room of the Vermont State House. It’s so prominent that this room is just called the Cedar Creek Room. Sarah’s great-grandfather Myron fought in that battle. She read to us from his diary:

Sarah: “…October 19th, the battle of Cedar Creek was fought. I was under fire all day… Saw Sheridan when he came up. His horse was covered with foam.” That’s what the Cedar Creek painting shows. “On October 23rd, we started for Vermont, about 100 of us. ..mustered out of the service November 19th, 1864 at Burlington”

Myron was a clever carpenter. About 5 years after he got home from the war, he built a house next to the creek. He married a woman named Julia, and they lived there for the next 50 years, selling produce from their garden.

Julia passed away about 5 years before the flood. So when the storm hit, Myron lived alone, watching the water fill up this house he had built.

Sarah: Right, and his furniture is all floating around in there. You know, some of it went out the window and down the river and was never seen again.

After the flood, when Sarah’s mom got home from Burlington, the family started to clean.

Sarah: They had to scrub floors, literally shovel out just junky mud. Everything that the water touched had to be scrubbed and cleaned.

Including rugs. Wet, heavy, room-sized rugs.

Sarah: I guess they tried to take them outside to just air for a while, and then of course they beat them with these rug beaters, but they were still heavy, heavy. It would be worth your soul to get them out of the house, much less hang them up, much less beat them.

When Sarah was younger, she would visit the house every summer. She told us evidence of the flood was still obvious decades later.

Sarah: I certainly remember handling lots of things in the house that were still gritty to the touch. You just had to look at the rugs and you could see that thin film of silt that was still left over that couldn’t be beaten out of the rugs and never left. It was in the crevices of the floorboards and it was there.

Myron passed away in 1928. Sarah wouldn’t claim that the flood killed her great-grandfather – living to 86 was pretty impressive for that time anyway. But she said the shock of the flood probably didn’t do him much good.

Sarah: They call it “daughtering out” when a family comes down to only daughters. The name isn’t going to be passed on and of course the name isn’t passed on with me either, but this family has devolved down to me and I was an only child. It’s very personal to me. I feel such an affinity for this man and I never met him, but I really have always felt close to him.

She donated the rug beater to the Historical Society in 2004, along with dozens of other objects from Myron’s house.

The Warners were one family affected by the flood, but the destruction reached across the state. Farmland was destroyed. Thousands of animals drowned. Eighty-four people lost their lives, including Lieutenant Governor Hollister Jackson, who was washed away after his car stalled out.

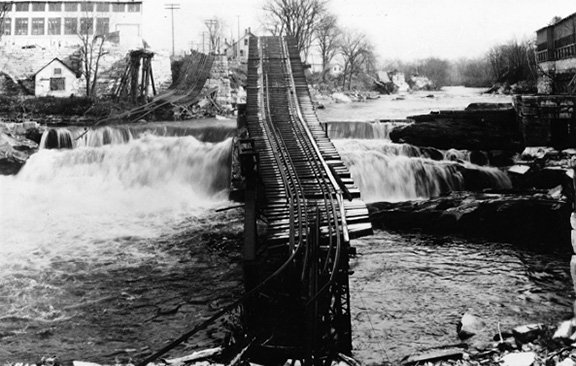

Nick Clifford: Roads, many of which were of course just plain dirt roads or at best gravel roads, roads were wiped out. Twelve hundred, I think the figure is twelve hundred and seventy-eight highway bridges came down.

Nick Clifford is a professor emeritus at Middlebury College. He and his wife Deborah wrote a book on the 1927 flood called The Troubled Roar of the Waters. He told us the flood devastated the state’s infrastructure.

Nick: Railroad bridges came down. Three months after the flood the Central Vermont was able to run a train very slowly and very carefully all the way from St. Albans down to White River Junction just to show that they could do it, but it was really a year before the Central Vermont was back up to its old pre-flood schedule.

In Montpelier alone, the estimated damage worked out to $400 for every man, woman, and child in the city. The total damage across the state was estimated at around $35 million. Adjusted for inflation, that would be almost half a billion dollars today.

Federal disaster relief agencies like FEMA didn’t exist back then. States like Vermont tended to pay for infrastructure repairs on their own. So it was a major shift when Governor John Weeks requested aid from the U.S. government.

Nick: Some people still thought it was a bad idea to take federal aid. “We run our own business and we don’t want the national government messing around with us.” But that was very much a minority view.

Vermont wasn’t the only state asking for relief that fall. A few months before Vermont’s rivers overflowed, an even more destructive flood ravaged huge sections of the Mississippi River Valley. The states affected by that disaster all requested federal aid, too.

If Vermont was going to get any aid, some of that money would eventually have to be paid back to the U.S. government. The decision fell to the president, who happened to be a native Vermonter: Calvin Coolidge.

Nick: Ultimately in May, 1928 Coolidge signed an authorization which brought the state two million six-hundred and fifty-four thousand dollars, which sounds like nothing today, but was a huge sum for a state that had never had a penny of federal aid.

I mean here was a poor state saddling itself with an enormous debt, which of course wasn’t paid off for another twenty years, and for many years it was the largest single item in the Vermont budget.

This money fundamentally changed the state’s relationship with the federal government. But it changed Montpelier’s relationship with other communities too.

Nick: This was at a time when certain towns, in the 1920s, certain towns for instance would not keep their roads open in the winter. “Why should we keep our roads open for other people just to drive through them?” There was local control – I mean, it’s still a big issue, but it was bigger in those days.

Some lawmakers saw this as an opportunity to build a completely new, state-run highway system, while others fought hard to keep roads under local control.

Nick: People very often say that the flood changed the state’s direction. I don’t think that’s true. I think what it did was to enormously speed up the rate of change that was already taking place. For instance, Weekes got through his bill for highway improvements, this rather slow, cautious, pay as you go highway improvement, but then came the flood, came the destruction of the highways. There was no point building the highways back up to where they’d been in 1926, and so the pressure for modernization was on. By the middle of the ’30s, certainly by the early ’40s, Vermont was famous for the quality of its roads.

Not every infrastructure proposal made it through the legislature, and some businesses never recovered. But piece by piece, the roads and bridges destroyed in the flood were rebuilt.

Nick: Glenn Andres, who’s a historian – art historian, architectural historian – has pointed out that in 1928, with these twelve hundred and seventy-eight bridges needing to be rebuilt, Vermont became what he calls the locus of a seminar on the latest technologies in bridge rebuilding.

So if you cross an old metal bridge in Vermont today, look around for a plaque. It will probably say 1928.

It was only a coincidence that a native Vermonter was the U.S. president when this disaster struck. But his response to the flood inspired a speech that’s become a part of Vermont’s identity.

As spring turned to summer in 1928, the year after the flood, some Vermonters urged President Calvin Coolidge to take his vacation in the state. Tourists would see that one could still enjoy a peaceful holiday in beautiful Vermont.

Instead, Coolidge chose to vacation in the woods of Michigan. But in September, he toured Vermont by railcar for two days – up the east side, across and down the west side – to look at the damage and the recovery from the great flood. The president’s caravan stopped in Bennington on September 21.

Jim Cooke is an actor who’s portrayed Calvin Coolidge in living history performances around Vermont since 1985. Jim estimates that over a thousand people heard Coolidge speak from the back of a rail car that day.

Jim: He spoke at some length before he delivered this – this was his closing.

The president began by noting that since the “great catastrophe” of the flood, the rail lines had been repaired, and that highways were open to traffic “for those who wish to travel by automobile.”

He then spoke these enduring words about his home state.

Jim: Vermont is a state I love. I could not look upon the peaks of Ascutney, Killington, Mansfield, and Equinox, without being moved in a way that no other scene could move me. It was here that I first saw the light of day; here I received my bride, here my dead lie pillowed on the loving breast of our everlasting hills.

I love Vermont because of her hills and valleys, her scenery and her invigorating climate. But most of all because of her indomitable people. They are a race of pioneers who have almost beggared themselves to serve others.

If the spirit of Liberty should vanish in other parts of the Union, and support of our institutions should languish, it could all be replenished from the generous store held by the people of this brave little state of Vermont.

If you’ve lived in Vermont for a while, you’ve probably heard these words before. Maybe you’ve seen them etched into the walls of the State House. Maybe you heard them spoken in 2011, after Hurricane Irene caused another wave of severe flooding across the state. Maybe you heard them after the 2016 election, when outgoing Governor Peter Shumlin and incoming Governor Phil Scott issued a joint statement on unity in the face of national discord, and quoted that entire last sentence.

If the spirit of Liberty should vanish in other parts of our Union…

Almost ninety years after his speech, Vermonters still look to Coolidge for inspiration. The words he spoke in Bennington that day may even be more famous than the catastrophic event that inspired them.